I am not a curriculum expert. I am an expert in achievement motivation and have spent nearly 20 years investigating its impact on learners and learning. Research shows that achievement motivation underpins students’ willingness to learn, their creativity, their persistence, and ultimately their success (e.g., Karabenick & Urdan, 2014; Wentzel & Miele, 2009) and thus it could be an important lens from which to evaluate a curriculum. I think the draft curriculum could have serious consequences for students’ intrinsic motivation in a way that can undermine learning for not only the outcomes named in the curriculum but for motivation for learning in general. As both a scholar and a mother to three elementary-aged children, this is a very big risk in my mind.

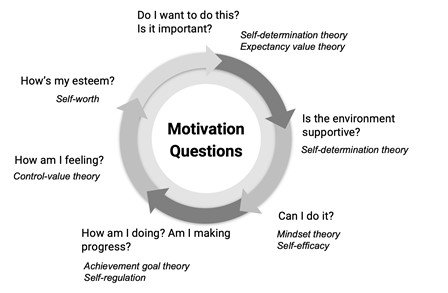

Because motivation is familiar to everyone, let me start by explaining how I engage with this concept from a scholarly perspective. I work largely from a social-cognitive perspective which means that I study motivation as rooted in social interactions and thought processes. I rely on theories that focus on the initiation and quality of goal directed behaviour and the resultant emotions and student outcomes (Elliot, Dweck, & Yeager, 2017). The following figure highlights the types of questions I explore as a motivation researcher and the wide range of applicable theories:

Based on decades of evidence (my own and from a massive field), I assert that not all forms of motivation are equal. The more students experience perceptions of competence, autonomy, and relatedness in their learning the more likely they will be intrinsically motivated and by extension work towards mastery, set ambitious goals, persist in the face of failure, enjoy their learning, and get good grades without suffering from extreme levels of anxiety and boredom (Elliot et al., 2017). So to what extent will students have a chance to experience competence, autonomy, and relatedness and its associated intrinsic motivation for learning in the new curriculum? From what I see, little.

Let’s take math as an example. Regardless of the evidence on inquiry-based math versus fundamentals and whether you interpret international rankings as falling or stable, the draft curriculum proposes a focus on “standard algorithms” which from a motivation perspective suggests students have little autonomy or choice over the ways in which they may encounter mathematical thinking. Can it work? Sure. But without some choice along the way we might have children who memorize quickly and are then bored by math because they don’t explore other routes to competence. Or children who struggle to memorize and come to believe that “they are just not good at math.” This type of fixed mindset undermines effort and persistence from grade to grade. I’m sure most of you can think of someone who in adulthood still avoids math because of these sorts of maladaptive beliefs. The same arguments can be made for any curricular area in which more content has been added – adding content means something goes, and part of what is likely to go is students’ time to be deeply and meaningfully intrinsically motivated to learn and understand the content (Ryan & Deci, 2017).

I don’t expect these types of psychological principles to be the driving force of curriculum development, but we have evidence that the design of everything in schooling from textbooks to classroom instruction and assessment has the potential to either support students’ competence, autonomy, and relatedness or thwart it (Ryan & Deci, 2017). Why would a curriculum be any different? In instruction and assessment actions like providing choice, using explanatory rationales, creating clear and correct instructions, reducing controlling language, and providing adequate time for appropriately challenging work have been shown to support competence, autonomy, and relatedness. These types of considerations could be extended to the domain of curriculum writing from which instruction and assessment then emerge.

Perhaps somewhat ironically, even though motivation is rarely (maybe never) a consideration in curriculum development, it seems at least some of the contributors to the curriculum are aware of these principles. The word “motivation” appears 51 times in the Physical Health and Wellness Curriculum with outcomes that are so broad my whole career could not adequately teach them or research their complex associations. Some outcomes include:

- Grade 1, Understanding, p. 9 Feelings and experiences can influence learning and motivation

- Grade 4, Skills and Procedures, p. 28 Connect how an individual’s development can have an effect on behaviours, motivations, emotions, and choice.

- Grade 5, Understanding, p. 30 Motivation can be internal and external and can change over time.

- Grade 6, Skills and Procedures, p. 39 Apply motivation strategies in a variety of contexts.

These learner outcomes allude to the very theoretical principles upon which my commentary is based – but they are restricted to the domain of physical education and wellness as if motivation is relevant for students to be physically active but not to learn. This shows a disconnect between what the curriculum outlines for students to learn and its design itself. Achievement motivation is named such because it is relevant in all achievement contexts and school is arguably the most ubiquitous achievement context in children’s lives. Everyone needs to find motivation to learn and what students have to learn is the curriculum. Why not support students’ intrinsic motivation right from the foundation of curriculum design?

My final comment shifts away from the motivational implications of this curriculum for learners, to attend to teachers. The empirical study of teacher motivation (Richardson, Karabenick, & Watt, 2014) is newer than that of students, but the work of teaching requires substantial intrinsic motivation similarly rooted in perceptions of competence, autonomy, and relatedness. From what I can see, teachers have responded clearly that they feel their competence and autonomy are undermined and that their relationships with students could be compromised by the draft curriculum as it is presented. By extension, their own intrinsic motivation is being eroded in ways that, despite their very best professional ethic, will trickle down to students because student and teacher motivation is often reciprocal (Skinner & Belmont, 1993). In other words, enthusiastic and motivated teachers tend to have enthusiastic and motivated students and the reverse holds as well. I see this curriculum potentially decimating intrinsic motivation in both students and their teachers in a way that could extend well beyond the elementary years because once the love of learning is lost, it is hard to reclaim.

References

Elliot, A. J., Dweck, C. S., & Yeager, D. S. (Eds.). (2017). Handbook of competence and motivation: Theory and application. Guilford Publications.

Karabenick, S., & Urdan, T. C. (Eds.). (2014). Motivational interventions. Emerald Group Publishing.

Richardson, P. W., Karabenick, S. A., & Watt, H. M. (Eds.). (2014). Teacher motivation: Theory and practice. Routledge.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Publications.

Skinner, E. A., & Belmont, M. J. (1993). Motivation in the classroom: Reciprocal effects of teacher behavior and student engagement across the school year. Journal of educational psychology, 85(4), 571.

Wentzel, K. R., & Miele, D. B. (Eds.). (2009). Handbook of motivation at school. Routledge.

Lia Daniels is a professor in the Department of Educational Psychology at the University of Alberta. She came to the University of Alberta in 2008 after completing a PhD in social psychology at the University of Manitoba. She is a quantitative researcher by training and work primarily from the theoretical perspectives of mindsets, achievement goal theory, control-value theory of emotions, and self-determination theory.