A version of this post was first published by Dr. Carla Peck on March 21, 2024 on https://carlapeck.wordpress.com/2024/03/21/an-analysis-of-the-k-6-social-studies-draft-curriculum-skills-procedures-through-the-lens-of-blooms-taxonomy-of-educational-objectives/

Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, initially developed by Benjamin Bloom and his colleagues in the 1950s, is a framework for categorizing educational goals and objectives (Bloom et al., 1956). While an older reference such as this might appear to be no longer relevant to educational concerns in the first quarter of the 21st century, the taxonomy “has had significant and lasting influence on the teaching and learning process at all levels of education to the present day” (Adams, 2015, p. 152). The taxonomy categorizes learning objectives into a hierarchical structure according to different levels of cognitive complexity, using verbs to identify the types of cognitive (or thinking) skills in each category. Of the three domains in the original taxonomy (cognitive, affective, and psychomotor), the cognitive domain is the most widely known and used. Using the taxonomy, curriculum developers (and teachers) can analyze the range of learning objectives in a curriculum (or a lesson/unit plan) and assess the range and complexity of the skills and abilities required of students as they engage in the learning process (Adams, 2015).

The taxonomy is often visually presented as a pyramid, implying that lower-level thinking must come before higher-level thinking, and that learning and thinking are linear. This is a common misconception about Bloom’s. Case (2013) provides an overview of three ways that Bloom’s taxonomy has become distorted over time and why that makes it a “destructive” theory (p. 196). It’s not the theory itself that Case objects to; rather, it’s how the theory has been misapplied by some educators that he finds problematic (or “destructive”). First, he argues that Bloom’s Taxonomy, when used incorrectly, can have the opposite of its intended effect of promoting more complex thinking if educators underestimate their students’ abilities and focus their teaching exclusively on lower-level thinking processes. Second, Case argues that when misapplied, the taxonomy can be used to justify a transmission teaching approach rather than one that aims to develop critical thinking and deep understanding:

The effect of an impoverished conception of understanding is to encourage a transmissive approach to content knowledge— that is, to encourage teachers to teach subject matter through direct transfer of information to the student. Not only is this not effective, in most courses there is so much content to “cover” that a transmissive approach typically leaves little or no time for meaningful opportunities for “higher order” thinking. (p. 198)

Lastly, Case argues that educators can have “misplaced confidence” (p. 199) that they are helping students engage in more robust thinking than may actually be happening: “The presumption that the verb clearly determines the kind of thinking that students actually perform fails to recognize that tasks at every level can be done in one of two ways: ‘critically thoughtfully’ or ‘critically thoughtlessly” (p. 199). I will provide an example of how this occurs with the use of the verb “hypothesize” in the 2024 draft K-6 Social Studies curriculum below.

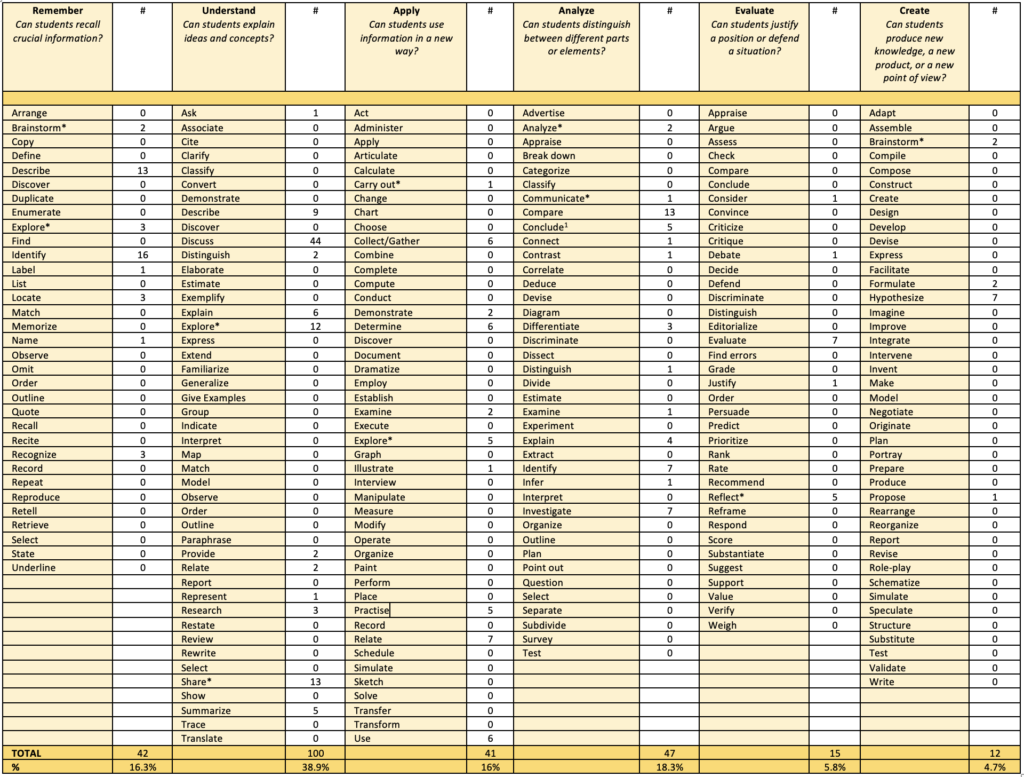

Over time, Bloom’s Taxonomy has undergone revisions to enhance its applicability and clarity. One of the most well-known revisions is the work done by Anderson and Krathwohl (2001). It is this revised version that formed the basis of the table below, which includes examples of verbs that indicate the cognitive process(es) that could be engaged in each category of the taxonomy.

Analysis of Verbs included in the “Skills & Procedures” Column

To analyze the use of verbs in the 2024 draft Social Studies curriculum, I used CTRL-F to search the curriculum for all 240 verbs listed below (that number includes duplicate entries). If a verb was listed in more than one of the taxonomy’s categories, I analyzed the skill in the draft curriculum where the verb appeared and used my professional judgement to assign that skill to a particular column. Each skill from the “Skills & Procedures” column in the draft curriculum is only counted once in Table 1.

As mentioned above, several verbs appear in more than one column. What differentiates their usage is the complexity of the thinking required to perform the skill. For example, “Model” appears in both the Understand column and the Create column. An example of a lower-level skill using the verb model is, “Model polite behaviour by using ‘please’ and ‘thank you’”. An example of a higher-level skill using the same verb is “Model municipal governance processes related to decision-making to make a decision about an issue in your community.” The first example is a lower-level skill because it only requires a student to repeat or mimic the teacher’s behaviour. The second example requires much higher-level thinking because a student not only needs to understand decision-making processes used by municipal governments, they also need to be able to recreate the processes in their own words and actions in order to demonstrate their understanding, and they need to use those processes to arrive at a decision about an issue in their community. This requires a student to engage in complex, creative, and critical thinking.

It was crucial, when analyzing the draft curriculum, to read across all three columns (Knowledge, Understanding, Skills & Procedures) in the section where each skill appeared. This revealed that even when higher-order thinking verbs like “hypothesize” are employed in the 2024 draft Social Studies curriculum, the way the Knowledge and Understanding columns are written reveal critical weaknesses in the use of the verb in the Skills and Procedures column. This means that the percentage of educational objectives in the top two categories of Bloom’s Taxonomy (Evaluate and Create) are not necessarily reflective of the complexity of the cognitive processes that would actually be in demand by a skill as articulated in the curriculum. Take, for example, this Skill in Grade 5: “Hypothesize the opportunities and challenges of establishing settlements along river valleys and coastlines.” On the surface, this appears to be a worthwhile skill for Grade 5 students, one that has the potential to promote critical thinking about how geography shapes settlement patterns. However, the Knowledge and Understanding columns do not support the skill of hypothesizing. The Understanding column, which is the learning target for this section of the Grade 5 curriculum, states, “Environmental features affect the distribution and movement of people.” The Knowledge column, which is what students are supposed to learn to lead them to this understanding, includes the following information:

- Ancient civilizations were complex societies that existed thousands of years ago (3000 BCE–500 CE) in different locations around the world; for example, Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, Rome, China, India, Mesoamerica.

- Many ancient civilizations grew along major river valleys because the geographical features supported agriculture, including abundance of water, fertile soil, moderate climate, proximity to trade and travel routes.

- Increased agriculture led to a shift from nomadic to settled societies.

- Regular flooding brought sediment to river valleys, which made the soil good for farming.

- Some ancient civilizations were established along coastlines because the geographical features supported settlement, including proximity to trade and travel routes and ports, fishing, natural protection provided by the landscape, moderate climate.

Students don’t have to “Hypothesize the opportunities and challenges of establishing settlements along river valleys and coastlines” because the answer has been provided for them in the Knowledge column (Opportunities: agriculture, abundance of water, fertile soil, moderate climate, proximity to trade and travel routes and ports, fishing, and natural protection provided by the landscape; Challenges: shift from nomadic culture, regular flooding). So, even when verbs that would typically signal higher-order thinking appear in the draft curriculum, close scrutiny reveals that their usage does not always mean higher order thinking skills are actually required. Of the seven times “hypothesize” is used in the draft curriculum, in only two instances will higher order thinking be required because the information and understanding necessary to “hypothesize” is not directly stated in the Knowledge or Understanding columns. In the remaining five uses of the verb, the Knowledge column contains the answer. If you’re curious, those two instances are: “Hypothesize social, environmental, economic, and political impacts of urbanization” (Grade 5) and “Hypothesize different ways countries around the world apply the fundamental principles of democracy” (Grade 6). To do this, students would need to conduct research and thinking critically to hypothesize various “impacts of urbanization” and how “different countries around the world apply the fundamental principles of democracy.”

Lack of Higher Order Thinking Skills

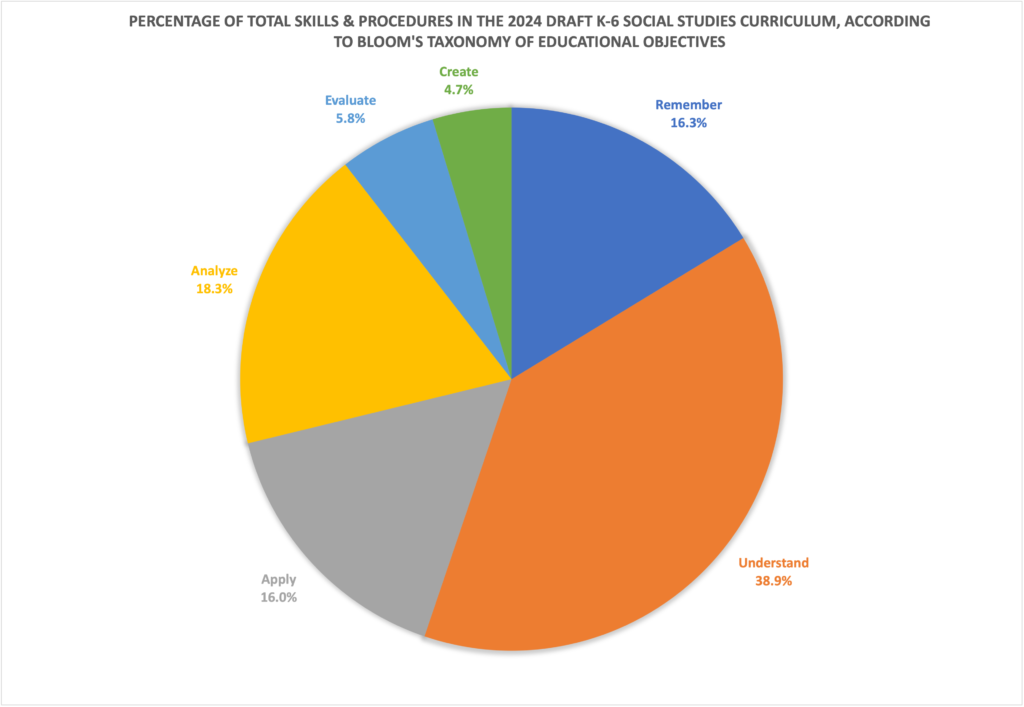

The 2024 draft curriculum embodies Case’s (2013) second concern with how Bloom’s Taxonomy is implemented by educators (or curriculum developers): “A widely held misconception of Bloom’s taxonomy is that it is seen to prescribe a necessary pathway for learning that requires moving up the hierarchy: teachers are to begin by front-end loading information acquired through “lower order” tasks before engaging students in more complex tasks” (p. 198). The implication here is that students can’t engage in more complex thinking without first accumulating large amounts of information, often signaled by verbs in the “Remember” and “Understand” categories of Bloom’s Taxonomy. Given more than half (55.2%) of the Skills & Procedures in the 2024 draft K-6 Social Studies curriculum fall into these two categories, and only 10.5% fall into the “Evaluate” and “Create” categories (Figure 1), it is clear that the assumption undergirding the entire curriculum is that thinking is linear, that before students can think critically and deeply, teachers must first pour copious amounts of knowledge into their heads.

I am not suggesting that the “Remember” and “Understand” categories are unimportant – of course they are. However, if we assume that students are unable to engage in sophisticated thinking before they accumulate large stores of knowledge, we are not only underestimating their capabilities, we are doing them a disservice. According to Case (2005), “students who receive information in a passive or transmissive manner are far less likely to understand what they have heard or read about than are students who have critically scrutinized, interpreted, applied or tested this information” (p. 45). The Critical Thinking Consortium (TC2), founded by Roland Case, emphasizes the importance of a “curriculum embedded approach” to teaching critical thinking, as well as the importance of teaching the “intellectual tools” that support critical thinking. These intellectual tools include background knowledge, but they also include developing criteria for judgement, critical thinking vocabulary, thinking strategies, and habits of mind, which Case and TC2 characterizes as “intellectual ideals or virtues that orient and motivate thinkers in ways that are conducive to good thinking, such as being open-minded, fair-minded, tolerant of ambiguity, self-reflective and attentive to detail” (p. 48). The crucial point here is that critical thinking skills are not skills that develop organically. They must be taught, and they must be taught carefully and well. Evans (2020) argues that, “improving students’ critical thinking skills and dispositions cannot be left simply to implicit expectations” (p. 10).

Of the 78 verbs listed in the “Evaluate” and “Create” columns in Table 1, only nine appear in the draft curriculum (for a total of 27 times, or 10.5% of all verbs in the Skills & Procedures column). Of these 27 instances, 21 of these “higher-order” verbs (cognitive processes) appear in Grades 4 through 6 only (6 in Grade 4, 6 in Grade 5, and 9 in Grade 6). The implication here is that young children in Kindergarten through to Grade 3 are incapable of higher order thinking, an assumption that does not hold up under scrutiny. In her review of literature on critical thinking, Lai (2011) noted that “empirical evidence supports the notion that young children are capable of thinking critically” (p. 24). Similarly, in a more recent review of literature, Evans (2020) concluded that “People begin developing critical thinking competencies at a very young age” (p. 8). Further, she noted that “research suggests there is no single age when children are developmentally ready to learn more complex ways of thinking (Silva, 2008), a finding consistent with both sociocultural and cognitive learning theory” (p. 8). There is ample support in the K-12 Social Studies research literature that young children can think critically and deeply – literature that the Minister of Education would be wise to consult (Brophy & Alleman, 2006; Levstik & Barton, 2001; Peck, 2010)

Conclusion

A close examination of the Skills & Procedures included in the 2024 draft K-6 Social Studies curriculum released by Alberta Education in March 2024 reveals a stark lack of skills and procedures that promote critical and complex thinking in students. In the rapidly evolving landscape of 2024 and beyond, where complex social, cultural, environmental, and political issues intertwine with everyday life, teaching critical thinking skills to elementary students has never been more crucial. Critical thinking is the foundation of informed citizenship and responsible decision-making. Learning to think critically from a young age supports students as they navigate being constantly bombarded by mis- and dis-information, learn to distinguish between fact and opinion, develop their capacity to research using credible sources, use sound criteria to make decisions, and engage thoughtfully with diverse perspectives. Nurturing critical thinking among the youngest members of our society is critical for shaping a future where citizens approach problems – and each other – with thoughtful consideration and a commitment to deep understanding.

References

Adams N. E. (2015). Bloom’s taxonomy of cognitive learning objectives. Journal of the Medical Library Association : JMLA, 103(3), 152–153. https://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.103.3.010

Anderson, L. W., Krathwohl, D. R., & Bloom, B. S. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of educational objectives. Longman.

Bloom, B., Englehart, M. Furst, E., Hill, W., & Krathwohl, D. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook I: Cognitive domain. Longmans, Green.

Brophy, J., & Alleman, J. (2006). Children’s Thinking About Cultural Universals. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Case, R. (2005). Bringing critical thinking to the main stage. Education Canada, 45(2), 45-49.

Case, R. (2013). The Unfortunate Consequences of Bloom’s Taxonomy. Social Education, 77(4), 196–200. (For an open access version of this article, visit: https://tc2.ca/uploads/PDFs/Critical%20Discussions/unfortunate_consequences_blooms_taxonomy.pdf)

CIVIX. (December 2023). Civics on the Sidelines: A National Survey of Canadian Educators on Citizenship Education. Retrieved on March 21, 2024 from: https://civix.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/CIVIX-Civics-on-the-Sidelines.pdf

Evans, C. M. (2020). Measuring student success skills: A review of the literature on critical thinking. National Center for the Improvement of Educational Assessment. Retrieved on March 20, 2024 from: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED607780.pdf

Krathwohl, D. R. (2001). A revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy: An overview. Theory Into Practice, 41(4), 212-218.

Lai, E. (2011). Critical thinking: A literature review. Pearson’s Research Report, 6, 50pp.

Levstik, L. S., & Barton, K. C. (2022). Doing History: Investigating with Children in Elementary and Middle Schools (6th ed.). Routledge.

Peck, C. L. (2010). Doing history at Fox Creek School. One World: The Journal of the Alberta Teachers Association Social Studies Council, 43(1), 4–8.

Stapleton-Corcoran, E. (2023). Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Center for the Advancement of Teaching Excellence at the University of Illinois Chicago. Retrieved March 20, 2024 from https://teaching.uic.edu/blooms-taxonomy-of-educational-objectives/

1 This is listed as “draw conclusions” in the 2024 K-6 draft Social Studies curriculum.

Dr. Peck researches the teaching and learning of history and citizenship, the role of identity in students’ historical understandings and uses of the past, and teachers’ and students’ understandings of democratic concepts.