A version of this post was first published by Dr. Carla Peck on March 21, 2024 on https://carlapeck.wordpress.com/2024/03/21/minister-nicolaides-its-time-to-listen/

On March 14, 2024, Demetrious Nicolaides, Alberta’s Minister of Education, announced a new draft K-12 Subject Overview and a new draft K-6 Social Studies curriculum. Albertans have been waiting on this draft since December 2021, when the March 2021 draft was repealed following extensive – and justified – criticism that included concerns that content was developmentally- and age-inappropriate, racist, and that the curriculum included only token mentions of multicultural groups, Indigenous peoples, and Francophone Albertans. With news of a new draft came the hope that the Minister of Education, along with his predecessor, had learned hard lessons about ignoring expertise. We now know that this is not the case.

With the release of the 2024 draft K-6 Social Studies curriculum, it is now clear that Minister Nicolaides is walking the same path as LaGrange on the curriculum file. What I didn’t realize until now is that the Minister’s calling is really in theatre. He likes to act like he listened to Albertans. And, he puts on a good show, full of excitement and big smiles at all he’s accomplished. At the event announcing the new curriculum, he boasted that he and his ministry consulted with over 300 “education and community partners, along with curriculum development specialists” to “help inform the development of a comprehensive new draft kindergarten to Grade 12 (K-12) social studies curriculum overview and draft K-6 social studies curriculum” and that the new draft incorporates the views of almost 13,000 Albertans about their priorities for a new Social Studies curriculum (collected via a survey).

While, it’s true that there were people consulted, what’s become clear is that their expert advice was not heeded. The Curriculum Development Specialist group, made up of professors and part-time instructors working at several universities across the province, published an open letter expressing their frustrations with the process and the curriculum that was the result of that failed process. As I read through the draft curriculum, I can understand their concerns. I was not a part of the Curriculum Development Specialist group although I did volunteer my time and expertise in a good faith effort to participate in the process. I was not selected. Lest anyone thinks my criticism is about the fact that I was not involved in the process, the truth is, I feel like I’ve had a lucky escape compared to my colleagues who were members of the group, many of whom I know well. Unlike their situation, the Minister cannot use my name to justify a fundamentally flawed process or product.

So, what’s the problem with the 2024 draft? Many of the same issues that were raised in 2021 remain.

It’s based on a weak understanding of “knowledge”

While the sparse introduction to “Social Studies” that is included on the first page of the curriculum points (in the briefest way) to key social studies goals such as developing critical thinking, understanding the past, and promoting active citizenship, the rest of the “knowledge-based” (p. 1) curriculum does not support these aims. How we think about what “knowledge” is matters. In this curriculum, “knowledge” just means facts. There’s a substantial literature in the field of curriculum development focused on what “powerful knowledge” means, and what we see in this curriculum is not it. “Powerful knowledge” includes content, yes, but it also includes helping students learn how knowledge is created (Young, 2008). In the case of social studies, that means learning how historians build knowledge about the world, how geographers do, how political scientists and anthropologists and economists create knowledge, and so on. That means we need to teach students different ways of learning about the world.

In history education, for example, powerful knowledge means more than the mere accumulation of facts and dates. It involves developing a framework that allows students to analyze, interpret, and critically evaluate historical events, understand the complexity of causes and effects, recognize the multiplicity of perspectives, and appreciate the interconnectedness of global cultures and societies. This type of knowledge equips students with the cognitive tools to question narratives, discern bias, and construct informed arguments, thereby empowering them as thinkers and citizens (see Young, 2008 and Chapman, 2021 ). As Counsell (2021) argues, “all educated citizens need not just facts about the past but history as a discipline” (p. 155).

It contains developmentally inappropriate material

Like the 2021 version, this draft contains content that is not developmentally appropriate. Why do 7-year-old children need to learn that “The government uses taxes to provide services for the community” (Grade 2)? The concept of “government” is too abstract for kids of this age, and I can’t think of any logical reason why a child needs to learn about taxes. Other concepts, such as imperialism, have been moved from junior high down to Grade 4. There are other examples, but you get the gist.

It’s Eurocentric

While there is no obvious racist language in this draft, it remains embedded in White settler colonial logic. What does this mean? The Oxford Bibliography explains settler colonialism as follows: “settler colonizers are Eurocentric and assume that European values with respect to ethnic, and therefore moral, superiority are inevitable and natural” (Cox, 2017).

The Grade 4 Curriculum, titled, “Colonial Canada”, is steeped in settler colonialism. Here’s a bird’s eye view of the content:

In the “Time and Place” section, under the learning outcome, “Students investigate changes in Canada’s political boundaries”, the following “understandings” are the learning targets:

- Canada’s boundaries have shifted over time.

- The establishment of New France began European colonization of Canada.

- Colonization benefitted European countries and colonists.

- Wars, rivalries, and treaties in Europe disrupted life in the colonies.

- Early legislation led to the foundation of Canada.

- Britain’s loss of control over the Thirteen Colonies impacted Canada.

- National identity can be developed when groups work towards common goals.

- Governments can make changes in response to the actions of the population.

- Events and legislation can influence migration.

- The Dominion of Canada was formed following negotiations.

“Colonization benefitted European countries and colonists.” I’ll say. But where is the learning target that ensures students also understand the devastating and enduring effects of colonization on Indigenous peoples in Canada? It doesn’t exist. In fact, there is very little content related to the history of Indigenous peoples in Grade 4. The “knowledge” tidbits that are listed are presented as neutral and do not reflect multiple perspectives on colonization, despite the fact that one of the so-called skills students are supposed to engage in is “hypothesize different perspectives on colonization.” The Knowledge column, which is what students are supposed to learn to lead them to the understanding that colonization benefitted European countries and colonists, includes the following information:

- Colonization involved European monarchs expanding empires by claiming land and establishing colonies on land already occupied by Indigenous peoples around the world, including in North America (imperialism).

- France founded the colonies of Acadia, New France, and Louisiana, and Britain founded the Thirteen Colonies.

- Colonists came to the colonies for a variety of opportunities; for example, access to farmland, business, religious freedom, quality of life, adventure

- Colonists brought belief systems and ways of organizing society to the colonies, including religions leadership education health care

- France and Britain benefitted from importing natural resources from the colonies in North America; for example, furs, lumber, agricultural products, minerals.

None of this prepares students to “Hypothesize different perspectives on colonization.” Only one perspective is required learning in the curriculum, leaving students with an incomplete understanding of colonization at best and a distorted understanding of colonization at worst. In a strong Social Studies curriculum, students wouldn’t have to hypothesize. They would be exposed to multiple perspectives on colonization in the curriculum and they would have opportunities to research and base their conclusions on reliable information, not “hypothesize” (guess) about it.

Another way that settler colonial logics appear in the Grade 4 curriculum is with the following “knowledge” students are supposed to learn:

- Colonists brought belief systems and ways of organizing society to the colonies, including:

- Religions

- Leadership

- Education

- Healthcare

This knowledge is presented as uncontested. The assumption that “colonists knew best” is baked in. These knowledge “outcomes” ignore the fact that Indigenous societies had well-established systems of governance, education, health care and spiritual practices, which European colonists deliberately attempted to erase via legislation (such as banning Potlatch ceremonies) and Residential Schools, among other formal and informal attempts at cultural genocide. There is no mention of Residential Schools in the entire K-6 curriculum, contravening the Truth and Reconciliation’s Commission’s Calls to Action that urged the Council of Ministers of Education to develop and implement “Kindergarten to Grade Twelve curriculum and learning resources on Aboriginal peoples in Canadian history, and the history and legacy of residential schools.”

It lacks important attention to skill development

Just as with the 2021 draft, the latest version of the K-6 Social Studies curriculum fails to include important Social Studies skills such as critical thinking, creative thinking, historical thinking, geographic thinking, decision-making and problem-solving, collaboration and cooperation, research skills, and communication skills. These skills teach important disciplinary ways of learning about the world (e.g., how do historians vs. geographers understand the world around them?) but they also teach students how to be deep and flexible thinkers who learn how to adapt and apply their learning to new contexts. The OECD argues that “creativity and critical thinking are needed to find solutions to complex problems” facing our society now and in the future. In this respect, the 2024 draft is sorely lacking.

In my elementary Social Studies curriculum and pedagogy course at the University of Alberta, I like to use the metaphor of an umbrella to unpack what we mean when we say “critical thinking” (or historical thinking, or geographic thinking, and so on). “Critical thinking” is an umbrella term under which many other types of skills fall. These include detecting fact from opinion, identifying mis- and dis-information, using criteria and logical reasoning to make a judgement (e.g., “which candidate should I vote for?”, “whose version of events should I believe?”), among other discrete skills. All of the “umbrella” skills listed in the paragraph above have subsets of skills, but there is no evidence of these in the latest draft of the Social Studies curriculum.

Instead, the curriculum presents a list of almost entirely low-level activities or test-like items such as “name the three levels of government” (Grade 2), “use scale to determine the distance between places on maps and globes” (Grade 5), and “summarize the structure and operation of provincial government” (Grade 6). For a more in-depth analysis of the quality of the thinking required by the “skills” included in the 2024 draft, read my analysis here.

It lacks a progression model

In addition to the problematic way that skills and procedures are conceptualized in the 2024 draft, a logical progression model is missing. There is little attention given to what skills students should develop in the early years in order to prepare them for more complex application of skills as they progress through the grades. Instead of a coherent plan for skill development, we are given a haphazard list of “things to do”.

Anyone who’s ever learned to play a sport or play an instrument understands this – you have to learn the basic skills of a play, like doing a lay-up in basketball, before you can do an alley-oop like Michael Jordan. For most people, skill development takes time and has to be thoughtfully planned and taught. This curriculum doesn’t do that. There is no thought given to sequence largely because there are very few skills at all.

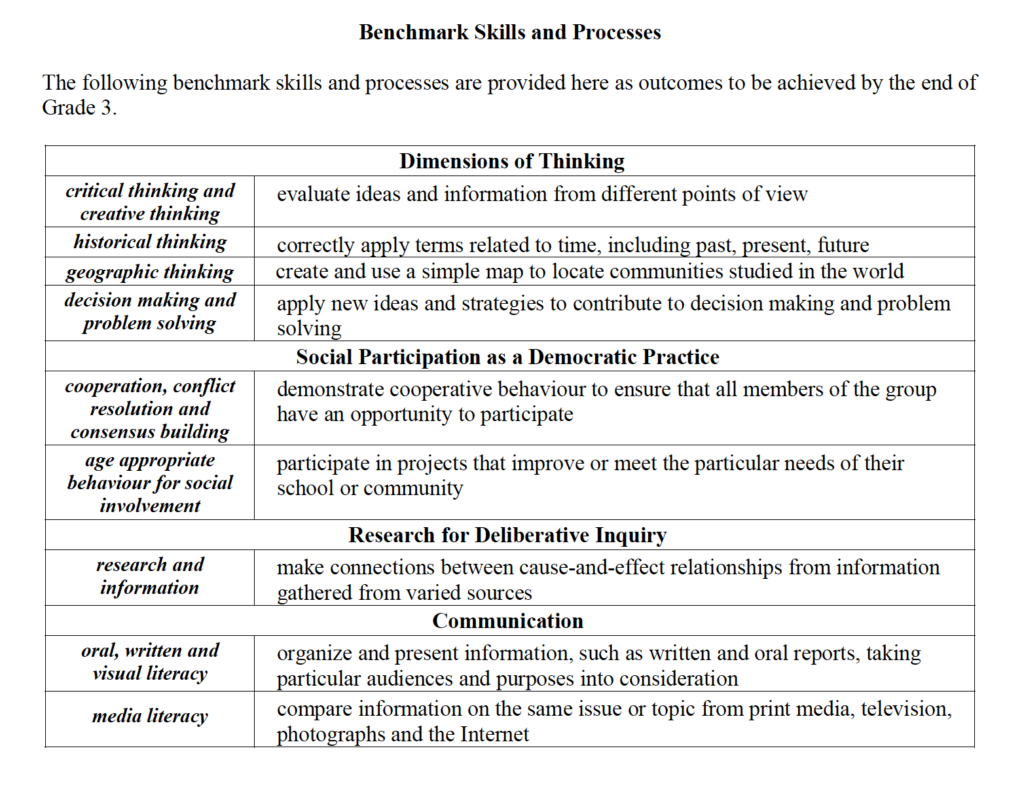

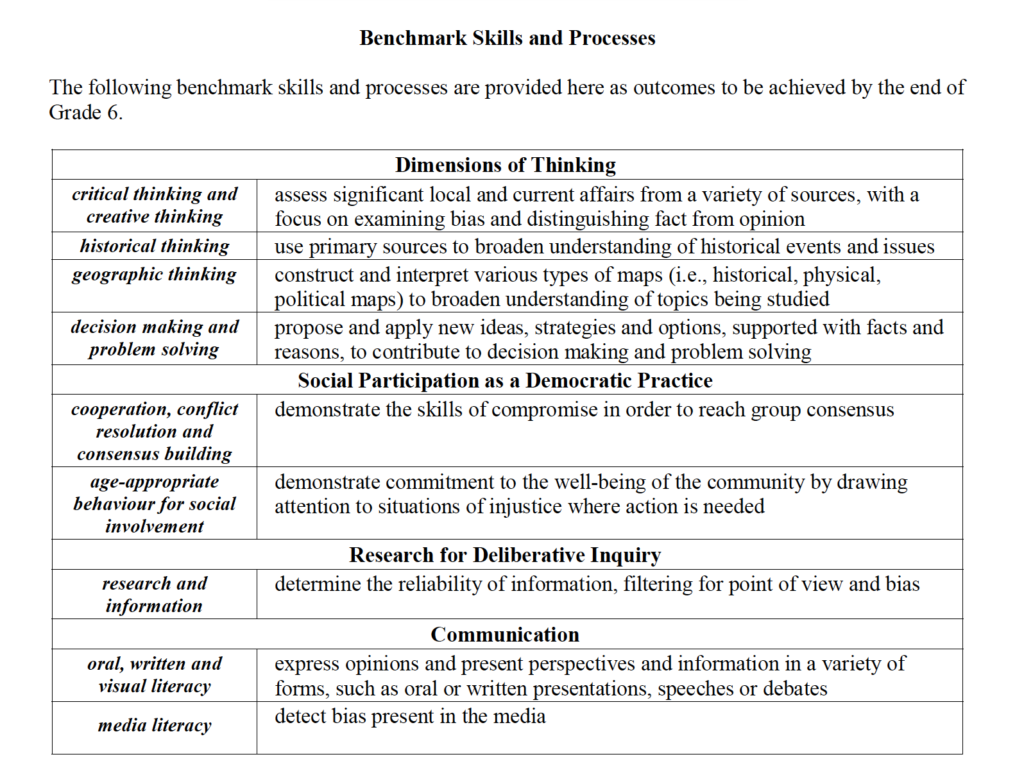

Compare this to the current Social Studies curriculum (released in 2005-2010) which identifies the skills that students will develop from Kindergarten – Grade 12. In this curriculum, clearly identified progression models are provided – with key stage outcomes (or “benchmarks”) identified for what skills students will have developed by the end of Grade 3 and Grade 6 (and later, Grade 9 and Grade 12).

Based on these larger categories of skills and learning targets, specific skill development is carefully planned from grade to grade. For example, this is what “historical thinking” looks like from K-6. In a few cases, a skill is repeated in a later grade to ensure that students have an opportunity to increase their proficiency in performing the skill. Additional skills are added from grade to grade to continue student growth in the specific category of skills (in this case, historical thinking).

| GRADE | Distinct “historical thinking” skills to be learned |

| K | – recognize that some activities or events occur at particular times of the day or year – differentiate between events and activities that occurred recently and long ago |

| 1 | – recognize that some activities or events occur on a seasonal basis – differentiate between activities and events that occurred recently and long ago |

| 2 | – correctly apply terms related to time (i.e., long ago, before, after) – arrange events, facts and/or ideas in sequence |

| 3 | – correctly apply terms related to time, including past, present, future – arrange events, facts and/or ideas in sequence |

| 4 | – use photographs and interviews to make meaning of historical information – use historical and community resources to understand and organize the sequence of local historical events – explain the historical context of key events of a given time period |

| 5 | – use photographs and interviews to make meaning of historical information – use historical and community resources to understand and organize the sequence of national historical events – explain the historical context of key events of a given time period – organize information, using such tools as a database, spreadsheet or electronic webbing |

| 6 | – use primary sources to interpret historical events and issues – use historical and community resources to understand and organize the sequence of historical events – explain the historical contexts of key events of a given time period – use examples of events to describe cause and effect and change over time – organize information, using such tools as a database, spreadsheet or electronic webbing |

It’s time to listen to the experts

The 2024 draft of Alberta’s K-6 Social Studies curriculum, while eagerly anticipated, missed the mark. This latest iteration fails to adequately address past criticisms, suggesting a performance of consultation without the substance of meaningful change. The Ministry of Education’s insistence on a weak interpretation of a “knowledge-based” approach to curriculum design, seemingly fixated on rote memorization of facts rather than the development of deep, critical, and powerful knowledge, stands in stark contrast to the needs of young citizens learning to navigate our dynamic, complex society. The curriculum’s lack of attention to developmentally appropriate content, its Eurocentric leanings that largely overlook the perspectives and worldviews of Indigenous peoples, and the absence of a progression model that scaffolds both skill and concept development through the grades, all point to a troubling disconnect between what students need to be successful and what teachers will be expected to teach.

In a time characterized by urgent social, political, economic, and environmental challenges and complexities, it is more important than ever to create a Social Studies curriculum that goes beyond superficial memorization of facts and instead promotes deep understanding. As Alberta looks to educate its young citizens, it must ensure that its curriculum is not merely a relic of past educational philosophies but a forward-looking document that empowers students with the skills, knowledge, and aptitudes required to navigate and shape the future.

I call on Minister Nicolaides to end the charade of consultation. It’s time to listen to the experts. Educational leaders are at your doorstep, willing to step up and create an inspiring Social Studies curriculum that educates learners who are as much at ease with evaluating the events of yesterday as they are with shaping the narratives of tomorrow. Won’t you let us in?

References

Alberta Education. (2024). Draft Social Studies Kindergarten to Grade 6 Curriculum. https://curriculum.learnalberta.ca/curriculum/en/s/sss

Alberta Education. (2005). Social Studies Kindergarten to Grade 12 Program of Studies.

Chapman, A. (2021). Knowing history in schools: Powerful knowledge and the powers of knowledge. UCL Press. https://www.uclpress.co.uk/collections/open-access/products/130698

Counsell, C. (2021). History. In A. S. Cuthbert & A. Standish (Eds.), What should schools teach? (pp. 154-173). UCL Press. https://www.uclpress.co.uk/collections/open-access/products/165025

Young, M. (2008). From Constructivism to Realism in the Sociology of the Curriculum. Review of Research in Education, 32, 1–28. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20185111

Dr. Peck researches the teaching and learning of history and citizenship, the role of identity in students’ historical understandings and uses of the past, and teachers’ and students’ understandings of democratic concepts.